It wasn’t the forehands.

It wasn’t the trophies.

And it definitely wasn’t the crowd.

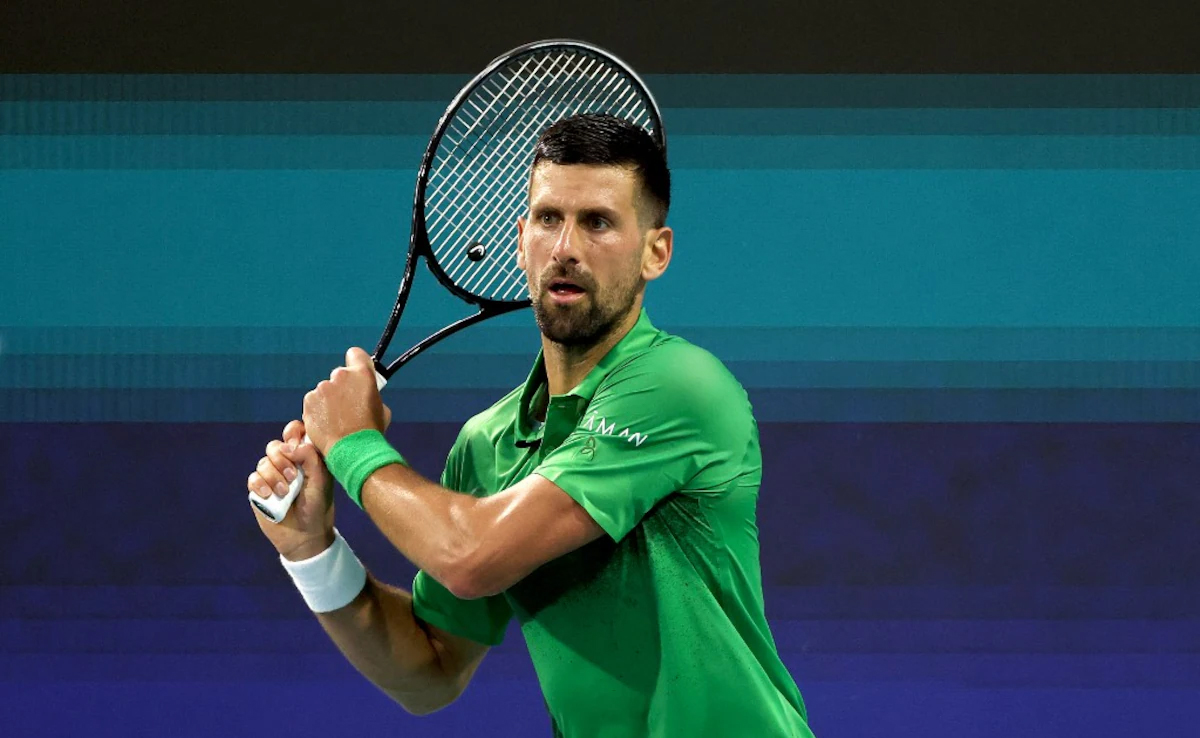

As Novak Djokovic marched through yet another Australian Open draw with a calm that bordered on unsettling, Jessica Pegula saw something most fans never stop to question. From the stands or the highlight reels, it looked familiar—efficient, dominant, inevitable. But from inside the tour, from the perspective of someone who understands the margins at the elite level, Pegula recognized a different kind of weapon at work.

One that doesn’t show up on stat sheets.

“What people miss,” she suggested, “is how much time he takes away from you—without ever rushing himself.”

That, in Pegula’s eyes, is Djokovic’s most dangerous skill in Melbourne: his control of tempo.

Djokovic isn’t just playing the ball anymore. He’s playing the clock in his opponent’s head.

Watch closely and you’ll see it. He doesn’t always hit harder or flashier shots. Instead, he subtly alters rhythm—slowing points just enough to force impatience, then accelerating at moments when opponents least expect it. Rallies stretch half a shot longer than comfort allows. Recovery time feels slightly shorter than it should. Decision-making windows shrink.

The result is pressure that creeps in quietly.

Pegula describes it as a “slow squeeze.” Nothing dramatic. No obvious collapse. Just a growing sense that you’re always a fraction late—physically, mentally, emotionally. Players start pressing on routine balls. They overhit safe targets. They rush serves not because the score demands it, but because Djokovic’s presence does.

He doesn’t chase winners. He invites mistakes.

What makes this version of Novak especially dangerous, Pegula believes, is how little energy he wastes enforcing that pressure. Earlier in his career, Djokovic’s dominance came with visible intensity—elastic defense, emotional fist pumps, physical endurance that wore opponents down. Now, the wear happens internally.

“He makes you feel like you’re running out of answers,” Pegula noted, “even when the match is still close.”

That’s the trap.

Against Djokovic in Australia, scorelines lie. A 3–3 set can feel like you’re already behind. A single lost service game feels irreversible. Not because it is—but because Novak makes it feel that way.

Pegula points to his decision-making under pressure as the clearest sign of evolution. Djokovic no longer goes for the spectacular unless the moment demands it. Instead, he chooses shots that maximize doubt on the other side of the net. Deep returns that land just inside the line. Crosscourt exchanges that refuse to give angles. Defensive balls placed with enough precision to turn defense into offense two shots later.

Every choice sends a message: You have to earn everything.

And earning points against Djokovic is exhausting.

By the second week in Melbourne, Pegula observed, players aren’t just tired in their legs—they’re tired in their thinking. Djokovic forces opponents to stay present for every point, every rally, every decision. One lapse of focus, and the match tilts.

That’s why Pegula believes this iteration of Djokovic may be more dangerous than ever. Not because he’s reinvented his game—but because he’s refined it to its quietest, most ruthless form.

“He doesn’t overwhelm you,” she implied. “He erodes you.”

The crowd barely notices. The rallies look normal. The scoreboards don’t scream drama. But inside the match, belief drains point by point. Players stop trusting patterns that worked against everyone else. They begin second-guessing instincts that carried them to Grand Slams.

And Novak? He never looks hurried.

At an event where chaos, heat, and pressure break even the strongest competitors, Djokovic thrives by becoming the calmest person on court. His most lethal weapon isn’t power or experience—it’s his ability to make others feel like time is slipping through their fingers.

By the time they realize what’s happening, it’s already over.

And that, according to Jessica Pegula, is what makes Novak Djokovic at the Australian Open not just dominant—but terrifyingly precise.